Shalom on the Shelf

Erev Rosh Hashanah Sermon, September 15, 2023

By Rabbi Mark Glickman

Tonight, here on the threshold of a new year, we have a lot to celebrate, but our world, as you know, is rife with conflict. There is a war in Ukraine, agonizing political unrest in Israel, violence on our own streets here in Calgary, and growing discord wherever we turn. Everything seems so difficult these days, everything is a battle. Will the fighting ever end?

I’m not sure that it will, but for some perspective on our current conflicts, I would like us to turn back to our history for a few minutes. And as we do, I’d like to introduce you tonight to two men, and a book. Maybe, as we meet these men, and take a look at the book, we can gain at least a little perspective.

The first man I’d like you to meet is a person named David Philipson.

Rabbi David Philipson

David Philipson was the youngest of the very first group of four Reform rabbis ordained in the United States. Born to German parents in a small town in Indiana in 1862, in his early teens Philipson moved to Cincinnati, Ohio to attend high school and to become a student at the Hebrew Union College, the newly-created rabbinical seminary in that city. In 1883, HUC ordained its first class of rabbis – four young men, the youngest of whom was Rabbi Philipson.

When Rabbi Philipson and his three classmates were ordained, there was a huge banquet held in Cincinnati to celebrate the event. The graduation banquet was a gala affair, and anyone who was anybody – both in American Jewry, and in the general non-Jewish Cincinnati community – attended it, fully decked out in their gilded age clothing: gowns, top hats, and black ties and tails, and all the rest.

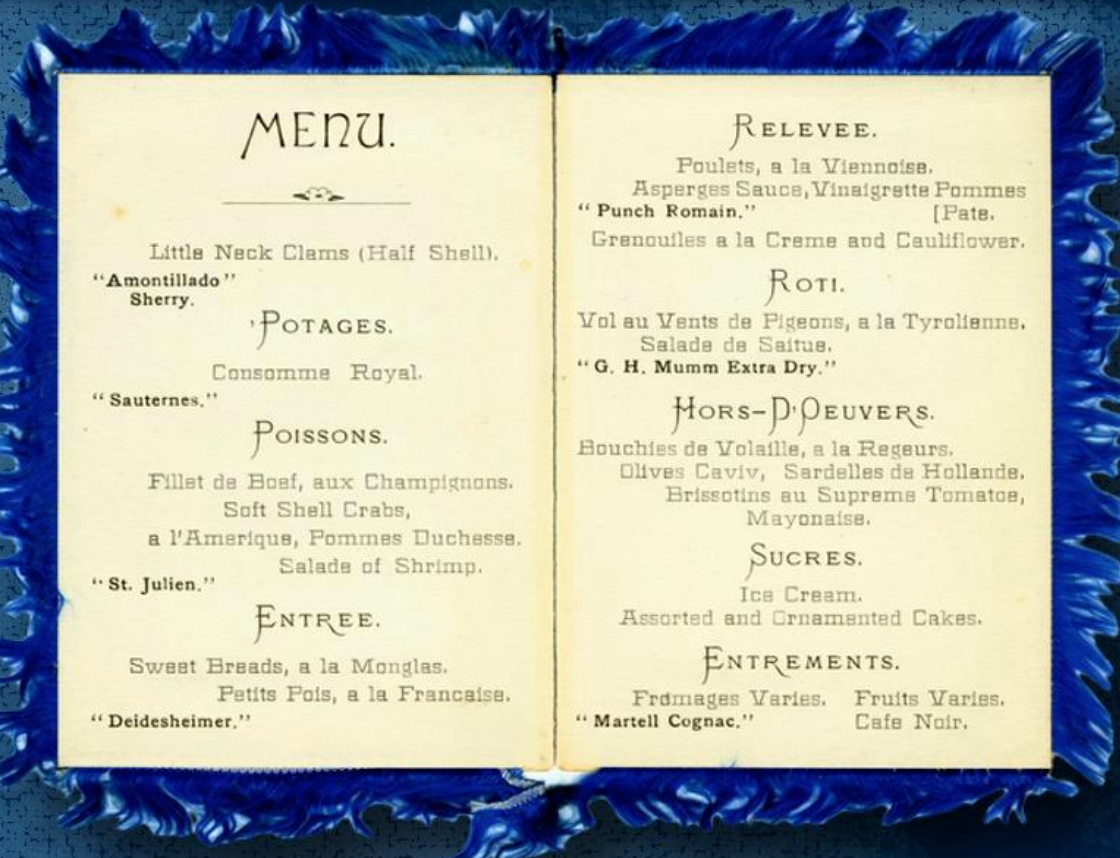

That banquet is worthy of a sermon in and of itself, but in brief, you need to remember that these were the early days of Reform Judaism. Reform Judaism was instituting revolutionary changes in Jewish life. Many people in America and Western Europe embraced these changes, but there were some who were concerned that it was changing too much and too fast. And that’s why the banquet was so scandalous. We still have the menu from that dinner, and you can see here why it caused such a fuss.

The Treyfe Banquet Menu

The appetizer (if you can make it out): little neck clams. The next course: filet of beef with soft-shell crabs and shrimp salad. And so the dinner proceeded. Sure enough, according to Rabbi Philipson’s recollections from later in his life, the people who were concerned about the speed of change in this newfangled thing called Reform Judaism stood up, stormed out, and – wouldn’t you know it – went off and started Conservative Judaism. In a sense, Conservative Judaism was born at the celebration of the ordination of four young men as Reform rabbis, one of whom was David Philipson.

Rabbi Philipson’s first pulpit was in Baltimore, MD. He earned a doctorate at Johns Hopkins University and drew acclaim as a leader in interfaith relations. During his tenure in Baltimore, Philipson became a leader in the American Reform rabbinate and was instrumental in composing the first platform of the Reform movement – a document called the Pittsburgh Platform of Reform Judaism. This statement, approved by the Reform Rabbinate in 1885, described our founding fathers’ understanding of what Reform Judaism stands for. It suggests that science and history aren’t antagonistic to our religion, but rather that they contribute to it…which was at the time, a revolutionary idea. It says that only the moral laws of Judaism are binding upon us today, not the ritual ones. It rejects Zionism, suggesting that we’re no longer a nation, but a religious community. It dismisses the ideas of heaven, hell, and the afterlife as foreign to Judaism, and it says that practices such as keeping kosher or wearing distinctive clothing are “apt rather to obstruct than to further modern spiritual elevation.”

How Reform has changed since then! What these rabbis described in the Pittsburgh Platform is what we now call Classical Reform Judaism. It was the Judaism of cavernous temples, robed choirs, and elevated rabbinic oratory. It was majestic, uplifting, and inspiring, just as its adherents felt a modern religion should be. And Rabbi David Philipson was one of its greatest American architects.

After five years in Baltimore, Rabbi Philipson moved back to Cincinnati, where he became rabbi of Bene Israel, now called Rockdale Temple, serving at that congregation for 61 years, until his death in 1949. There, he continued his interfaith work, battled corruption in the local city government, and fought antisemitism wherever he could. He edited the Reform movement’s Union Prayerbook; he wrote a comprehensive history of the Reform movement, which was still in use as recently as my own stint in rabbinical school. And as vehement he was in his opposition to antisemitism, he was also an anti-Zionist. To him, Judaism was a religion; America was his nation. “No man,” he wrote, “can be a member of two nationalities.” In 1897, he and his allies issued a statement in response to the first Zionist Congress in Basel asserting that “America is our Zion,” not the land of Israel.

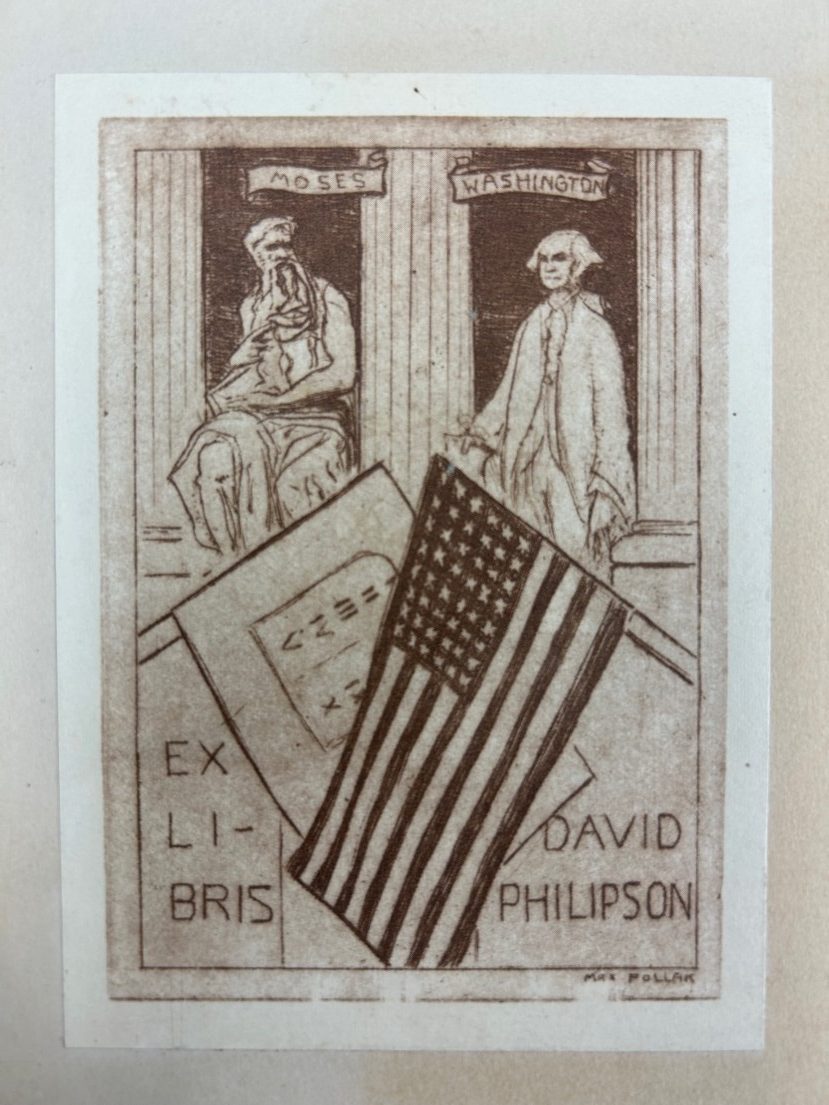

David Philipson Bookplate

My uncle, Rabbi Robert Marx, studied with Rabbi Philipson shortly before Philipson’s death in the late 1940s and was able to get a few books from Philipson’s library after he died, and Philipson’s bookplate says it all.

It shows two flags – the American flag, and a Jewish flag. The American one is in front. It also shows two statues, one of Moses, and the other of George Washington. Moses is slightly behind that first American president, looking respectfully on him from the rear.

David Philipson wrote many books, taught at the Hebrew Union College, he served as president of the Central Conference of American Rabbis. Not surprisingly, he was widely known as the “Dean of the American Rabbinate.”

The other man I’d like you to meet tonight was another giant of the 20th-century Reform rabbinate – Rabbi Stephen Wise.

Rabbi Stephen Wise

Born in Budapest in 1874, Wise migrated to New York with his family as a child, but returned to Europe as a young man, receiving his rabbinic ordination and a doctorate in Vienna in 1893. He served a pulpit in New York and another in Portland Oregon before coming back to New York and founding “The Free Synagogue,” today known as the “Stephen Wise Free Synagogue.” (There were no dues; everyone paid what they could; don’t worry we’re not going to do that here.) For many years, the congregation didn’t have a building, and met instead for their weekly worship at – where else? – Carnegie Hall.

And from early on, Rabbi Stephen Wise was a colossus. In 1909, he became a founding member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People – the NAACP. In 1915, he helped found the American Committee on Armenian Atrocities. He fought for the rights of coal miners during labor disputes in the 1920s, speaking out for the workers even though many mine owners those workers opposed belonged to his own congregation.

In the early 1940s, Wise was one of the first American Jewish leaders to become aware of Nazi atrocities against Jews and fought with all he had on behalf of European Jewry. He spoke widely to draw attention to their plight, he traveled to Washington DC frequently to meet at the White House with his “friend Franklin” – Franklin Delano Roosevelt – and advocate for American support on their behalf, and in 1942 Wise convened tens of thousands of people at a rally at Madison Square Gardens to draw attention to their cause.

Stephen Wise was a master orator, speaking in the stentorian tones of speakers trained to address audiences before the era of electronic amplification. Here, in one of the few films available of him, from a newsreel about the Kristallnacht pogrom in Germany in 1938, you can get a sense of what he was like.

And unlike David Philipson, Stephen Wise was an ardent Zionist. He was the president of the Zionist Organization of America, he was Chairman of the United Israel Appeal, he founded and was president of the World Jewish Congress, which supported Zionism however it could.

As I mentioned, early Reform was largely opposed to Zionism, but Wise fought with all his might for the Reform movement to support the creation of a Jewish state. And realizing that the Reform movement’s seminary in Cincinnati, the Hebrew Union College, taught rabbinic students from its anti-Zionist perspective, Wise went and started his own seminary – the Jewish Institute of Religion, in New York. Later, after Wise’s death, most Reform Jews embraced Zionism, and the two seminaries merged, adopting a new mouthful of a name befitting its history – The Hebrew Union College – Jewish Institute of Religion.

Rabbi Stephen S. Wise died in 1949, and just a couple of months later, so did Rabbi David Philipson.

By this time, the State of Israel had come into being, and, as I said, the Reform Movement had overwhelmingly adopted it, ending up in favor of the Zionist perspective of Stephen Wise, and against the anti-Zionism of David Philipson.

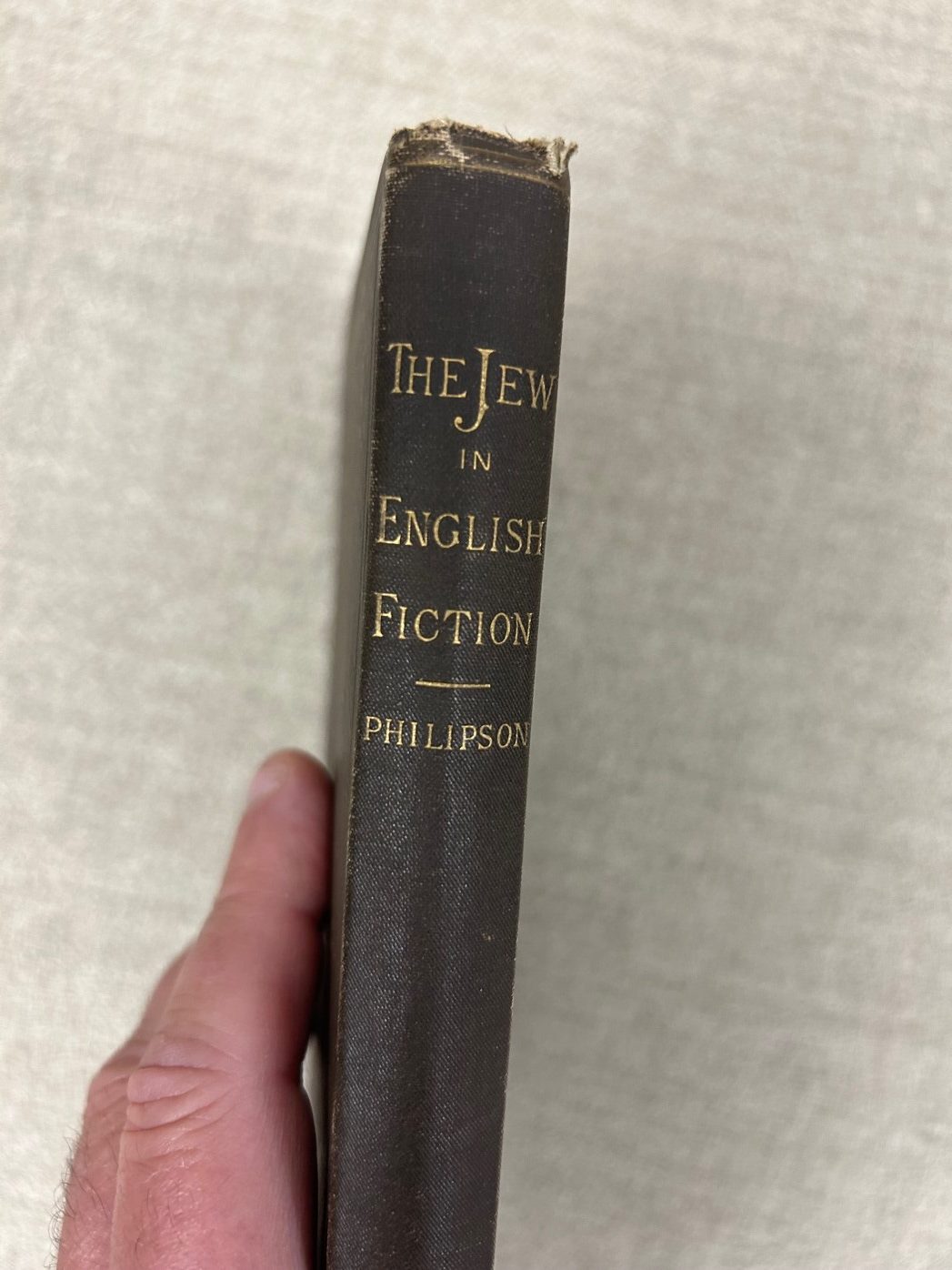

And now for the book, I’d like to show you.

I bought it online several months ago. It’s called The Jew in English Fiction, it was published in 1889, and it was written by David Philipson. As I mentioned, Philipson wrote several books, but this one was his first. When it came out, he had just begun serving his congregation in Cincinnati, and he was 27 years old.

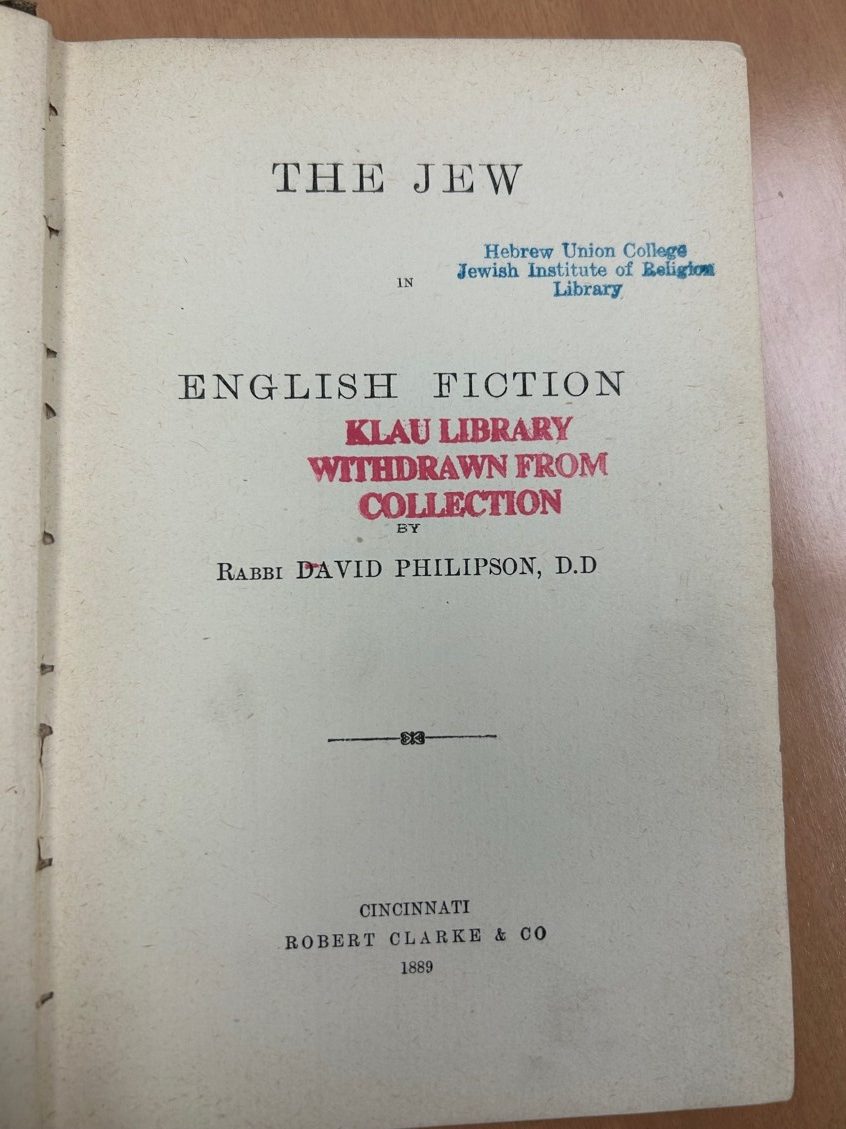

Hebrew Union College Library Stamp

This particular copy bears the stamps of the library at the Hebrew Union College, of which he was one of the first ordinees, and where he taught rabbinic students later in his career.

It’s safe to say that in some ways this book is subtly imbued with anti-Zionist ferment. Its author was a lifelong anti-Zionist. Its owner, the Hebrew Union College, was, at the time of its publication and for a couple of decades afterward, an anti-Zionist institution. And its content describes the significance of Jewish life not in the land of Israel, but in England – particularly in British literature. The book doesn’t explicitly address the question of a Jewish state, but it does speak of the richness of diaspora Jewry, and you can almost feel the anti-Zionism oozing out from between its pages.

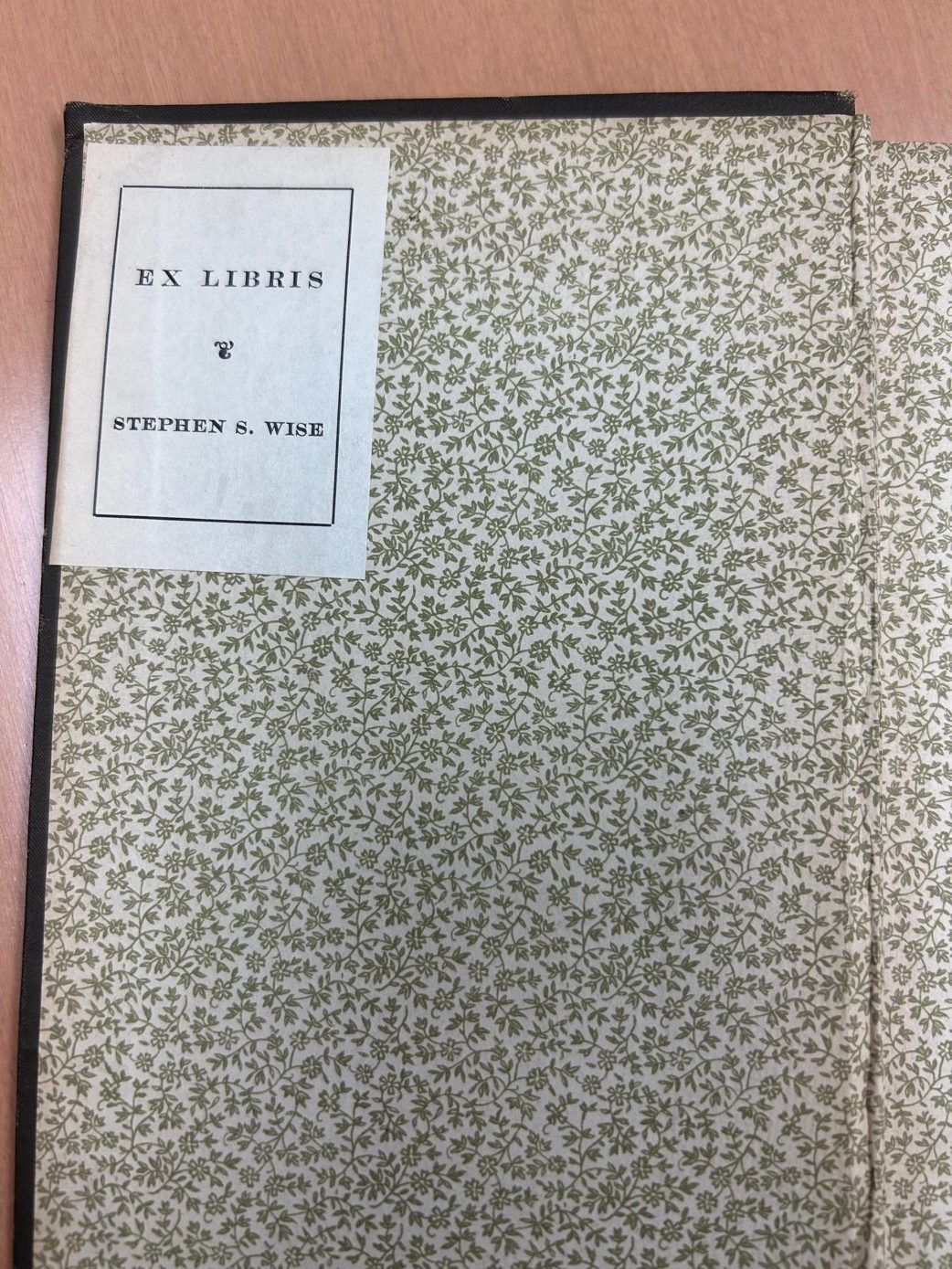

Examining the book further, however, you realize that the Hebrew Union College was probably its second owner, because, on the inside front cover, you can find the bookplate of its first owner. Who owned this book first? You can see it here:

Rabbi Stephen Wise Book Plate

Ex Libris (from the library of) Stephen S. Wise. This was Stephen Wise’s personal copy of The Jew in English Fiction.

Ideologically speaking, Stephen S. Wise and David Philipson were at each other’s throats over the Zionism issue for most of their careers. Philipson was practically part of the woodwork at HUC, and Wise went so far as to open a rival seminary. During the first decades of the 20th century, as Zionism grew in strength, the arguments over the idea raged throughout our Reform movement…and these two titans were each at the helm of the opposing sides of the battle. It was a huge controversy. Philipson probably could have gotten a job at one of the big New York congregations, but a city as small as New York wouldn’t have been nearly big enough to hold these two giants!

In time, as we’ve noted, the controversy abated, and my guess is that after Wise’s death, and after the two seminaries merged, parts of his library were donated to HUC-JIR, and this volume eventually made its way to Cincinnati.

Given the nature of the argument and the size of the personalities of these two men, you would think that there would still be sparks flying from this little volume. If New York wasn’t big enough to hold them, how could this book be? But you know what? No sparks fly from these pages. Instead, the book just sits quietly on my shelf, snug and safe alongside hundreds of others. The arguments of yesteryear no longer rage between these two men – at least not like they did – and in fact, those controversies are now so quiet that it took me several minutes tonight even to describe what they disagreed about.

“That is why I have always felt such deep attachment to libraries,” Elie Wiesel writes. “Here, within these walls, there is peace. The old quarrels subside…. All these writers and teachers, all these thinkers and lawmakers who engaged in disputations during their lifetime, now accept one another’s views with tolerance and serenity. Because of the books? Because of the silence. Here, words and silence are not in conflict—quite the contrary: they complete and enrich one another. Is it possible? In our tradition—it is.”

Our battles – they erupt with ferocity today, but later they grow quiet so quiet sometimes, that we need to remind ourselves what we were fighting about in the first place.

Remember your schoolyard fights from when you were a child? Many of them were over real hurts, and many – not all – seem almost quaint as we look back at them years afterward. The professional conflicts that we once fought so angrily? They have a way of calming down as they become distant memories. Not always, but often. Even divorced couples, who once fought with such untrammeled vengeance – over the years, the anger often subsides, leaving both parties able to be civil with one another. Even friendly.

My friends, in the year ahead, and in future years as well, you will certainly find yourself having an argument or two…and probably many more than that. And as important as these arguments might be, I invite you to look at them through the prism of this little book. In thirty years, or in fifty or one hundred, where will this conflict be then? What will the lasting effects of your argument be? I’m not saying that you should refrain from fighting – after all, in the days of Wise and Philipson, discussing the creation of a Jewish state was hugely important. I’m only suggesting a little humility – that you remember that however passionately you argue and however crucial your cause, someday, somehow, you and your opponents might end up snuggled together on the shelf of a rabbi in Calgary, Alberta.

The wars of yesterday become the skirmishes of today, and the skirmishes of today can become the fascinating footnotes of history tomorrow. Look what happened here. Two lions who once roared so loud now sit quietly together, and tonight we can learn from them both.

May this year be a year in which we all can transform memory into knowledge. Then it will be a good year, indeed.

Shanah Tovah.