The Canadian Council of Reform Judaism (CCRJ) is organizing a Canada-wide Selichot service and YOU are invited to attend.

Save the date: Sat Sept. 12, 7:00 pm MT

7:00-7:30 pm –Special Guest speaker Dr. Larry Hoffman

7:30-8:00 pm – Discussion facilitated in Zoom breakout rooms

8:00 pm – Havdalah

8:15 pm – Selichot Service

Contact the Temple Office for more information.

Yom Kippur Morning Sermon

Temple B’nai Tikvah

5780/2019

Rabbi Mark Glickman

Today, on this holy occasion, and in this holy place, I’d like for us to spend some time thinking about Jerry Springer.

For those of you not blessed to be acquainted with this man’s oeuvre, from 1991 to 2018, Jerry Springer was the host of a syndicated tabloid talk show on TV, featuring episodes with such memorable titles as “I Faked My Pregnancy,” “Out of Control Catfights,” “Twin Brother Betrayal,” and about 4,000 others that would be inappropriate for me to mention from the bimah.

Jerry Springer will long be known and remembered for his TV show, but that’s not all he was ever known for. He was born in England in 1944 to two Holocaust refugees, and at the age of four, he moved to the United States. He grew up in New York, went to Law School at Northwestern University, and as a young man, he worked as a political advisor to Robert Kennedy. After Kennedy was assassinated, he moved to Cincinnati, Ohio, where he began working as a lawyer. Soon, Jerry Springer got involved in politics, and in 1971, he was elected to the Cincinnati City Council. His career went well until, in 1974, Springer chose to spend some time with a woman he shouldn’t have spent any time with…and he paid her with a check. (Watch 1981 Jerry Springer Mayor of Cincinnati Interview.)

He got caught, he publicly confessed to what he had done, he apologized, he resigned from the city council, and by all accounts, his political career was over.

Except, it wasn’t. Because then a remarkable thing happened. Springer kept on talking about his misstep. He fully was open about it; he acknowledged that what he had done was wrong, and he owned up to the pain he had caused. The following year, in 1975, he ran for election to reclaim his council seat, and he won. And then, two years after that, Jerry Springer became the mayor of Cincinnati. Politics are usually complicated of course, and there were many factors that contributed to Springer’s comeback. But at some profound level, his redemption was rooted in the fact that the Cincinnati community appreciated Jerry Springer’s honesty and what was, by all accounts, the sincerity of his apology. By the time I moved to Cincinnati for rabbinical school in the mid-80s, Jerry Springer was doing a nightly news commentary – liberally minded, thoughtful, and a far cry from his later TV show.

Say what you will about his dumb and often offensive TV show, the political biography of Jerry Springer in the 70s and 80s is, at least in part, the story of the power of genuine apology. And genuine apology is particularly important these days because there’s so little of it. Some people try to apologize – at least ostensibly – but so often their attempts to apologize are, shall we say, sorry affairs.

A famous actress explains a racist tweet by saying she posted it because she was on Ambien at the time. A major Hollywood producer responds to hundreds of harassment charges with “I so respect all women and regret what happened.” One of the most powerful leaders in the world brags of assaulting women, and, when called to task, says, “I’m not proud of it, but this is locker room talk.” The list of half-hearted, disingenuous statements passed off as apologies could keep us here all day.

Part of the problem with apologies is that the English language doesn’t always serve us very well here. In English, you see, the term “I’m sorry,” can mean one of at least two things – it can refer to regret, or apology. If, for example, I were to say, “I’m sorry your grandmother died,” I probably wouldn’t have intended that statement to be an apology for your grandmother’s death (unless I killed her, I suppose) – no, it would have been a statement of regret. It means that I’m unhappy that grandma died, that I feel for you, that my heart is with you. It’s a statement of sympathy rather than apology. And conversely, if I were to say “I’m sorry for bashing up your car,” that’s a statement of apology. It’s not that I sympathize with you because your car is damaged. No, here, I’m owning up to my own responsibility for the harm I inflicted on you.

This duality of meaning – the fact that “I’m sorry” can mean either “I sympathize” or “I apologize” – provides a huge opportunity for people who want to weasel out of genuine apology. For someone who has done something wrong, and who wants people to think that they’re truly repentant when they’re actually not, this is pure gold. It allows them to make a statement of regret and dress it up to look like a heartfelt apology.

They say, “I’m sorry if I insulted you,” which might sound like an apology, but it really says “It’s too bad that you’re so thin-skinned as to be hurt by my innocuous comment.” They say, “I’m sorry, but when you said you like disco, I couldn’t help but call you an idiot,” when they really mean, “Don’t blame me – you’re the one who likes disco.” They say, “I’m sorry you were hurt when I said that dress looked a little tight,” when they really mean “My, my…we’re getting a little sensitive about our weight, aren’t we?”

Let’s be clear, the world “if” has no place in apologies. When someone says, “I’m sorry if…,” then they’ve made their statement conditional, and subtly put the blame of the conflict on you. Chances are that it’s not a sincere apology. Similarly, the word “but” rarely belongs in apologies, either. When a person says “I’m sorry, but…” then they’re probably trying to excuse their behavior, and chances are that it’s not a sincere apology. The same is the case with the word “you.” When someone says, “I’m sorry you…” then in all likelihood, they’re passing the blame for what they did from them to you, and chances are that it’s not a sincere apology.

There are a lot of bad apologies out there, but what makes for a good apology? Well, rabbis throughout the ages have struggled with this question, and they’ve taught us a great deal of insight and wisdom as to how to say I’m sorry in a way that really counts. I’ve studied these lists, and I’ve been able to distill much of their teaching down to three requirements – three traits that an apology must have if it’s to be a good one. Conveniently, each of them begins with an R.

The first R that a good apology demands is responsibility – you have to take responsibility for what it is that you did wrong. You have to not only own up to the fact that you fell short, but you also need to acknowledge exactly what it is that you did. That’s why every good apology needs to begin with the apologizer saying something to the effect of “I’m sorry that I _____.” Not “I’m sorry if…”; not “I’m sorry but…”; not “I’m sorry you…,” but “I’m sorry that I…” and then fill in the blank. In other words, you need to own up to your own responsibility for your misdeed. You need to be concrete about what you did wrong, you need to be specific, and you need do so without making any excuses.

Don’t say, “I’m sorry if what I said about that dress making you look fat hurt you.” Say instead, “I’m sorry I made that comment. It was insensitive and wrong, and I shouldn’t have said it.” Don’t say, “I’m sorry I betrayed your confidence, but I just got a little carried away.” Say instead, “I’m sorry I betrayed your confidence. Period. You trusted me, and I should have honored your trust.” Don’t say, “I’m sorry you were offended at my off-color joke.” Say instead, “I’m sorry I told an inappropriate joke.”

Own up specifically to your misdeeds, and your apologies can really count.

At this time of year on social media, I see a lot of posts – sometimes even from rabbinic colleagues of mine – saying things like “To anyone I’ve knowingly or unknowingly wronged during the past year, I apologize.” Let me be clear – I’m not going to say that or anything like it to you. Instead what I’ll say is this: “If I’ve done anything hurtful to you during the past year – or even before that, I suppose – please tell me about it. It might be that you misinterpreted something I did, or that we had some sort of a communication glitch, or that you’re simply being a ridiculous kvetcher, in which case you’re not going to get any kind of an apology from me at all. But it could be that I really did do something wrong, and in that case, I’ll do everything I can to offer you the genuine apology that you deserve. But I can’t apologize for something I don’t know I did, and for me to offer you a blanket apology for something I might have done, without acknowledging the specific wrongdoing for which I’m offering it would be worthless and meaningless.”

Apologies need to take responsibility for specific wrongdoings, and they need to do so without excuses.

The second R of a good apology is recognition – recognition of the harm that your misdeed caused. What’s wrong with responding to the release of recordings in which you brag of assaulting women by saying “I’m sorry, it was just locker room talk”? Yes, at one level you apologized, I suppose, but the way you did so was dismissive of the harm that your behavior caused. The fact is that countless women have been victimized by such groping and unwelcome advances, and that each such act has a way of creating horrible pain, some of it irreparable. To apologize for such acts – to really apologize – demands that you recognize and acknowledge this harm. You need to give voice to it, to show that you understand the depth of the injury you caused. And to refrain from doing so is to invalidate your apology.

Imagine a person saying, “Yes, it was me who pushed your husband off the bridge into the raging waters below. [Shrug] Sorry.” Or “By the way, honey, I’ve been having an affair with your best friend for the past two years, and I apologize. Wanna out to dinner?” Or “Yes, I’ll admit it, I embezzled the money and persuaded the boss it was you. Now can we be done with this?” None of those apologies works, because apology demands empathy. It demands that we show ourselves to be sensitive, and aware of the damage our misdeeds do. Only when accompanied by such a recognition can our apology work.

Finally comes the third R of a genuine apology – restitution. Once you’ve owned up to your responsibility for what you’ve done, and once you’ve shown that you recognized the harm you’ve caused, then you need to offer to make the victim of your misdeed whole again – you need to compensate them for the damage. Sometimes, such compensation is easy. If I spill wine on your clothes, I need to get those garments cleaned or replace them. If I drive my car into your garage door, I need to get the door fixed. If I sell you a faulty object, I need to replace it.

But of course, sometimes it’s not so easy. What if I break a confidence with you? What if we’re joking around, and, without thinking, I say something really hurtful to you? What if I do something so horrible to you that I couldn’t ever adequately compensate you for what I’ve done?

In these cases, it’s never easy to calculate fair compensation. But even when it’s complicated, the wrongdoer needs to try to figure out how to do right by the victim of his or her offense. There are couples, for example, whose relationships successfully recover from horrible infidelities, and while the recipe for the recovery of those relationships always has many ingredients, one of the most important is a willingness on the part of the adulterer to make things right. Can you ever heal a relationship after you’ve said something hurtful to the other person? Yes, you can. It’s not always easy, and sometimes it takes time, but when you’re willing to do right by that person, the healing is always possible; redemption can happen.

Remember, compensating our victims – paying them for the damage we cause – is one of the most important steps in teshuvah, repentance. And Judaism says that teshuvah is possible for just about every sin we commit, even for some of the really bad ones.

Think about the awesome nature of what Jerry Springer was able to do. He took a career in shambles, and, with the heartfelt recitation of what was effectively two words – I’m sorry – he recovered it, becoming (for better or for worse) a very successful person as a result. Redemption is possible; healing can happen; repair is achievable – even amidst the wreckage we often make of our lives.

All we need to do is apologize and apologize well. Doing so isn’t always easy, but when we succeed, then just think of all the great things we can accomplish.

Shanah Tovah

Erev Yom Kippur Sermon

Temple B’nai Tikvah

September 29, 2017 – Tishri 10 5778

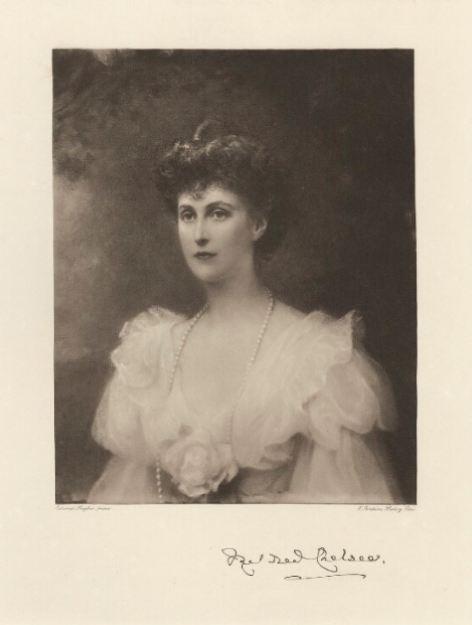

Her given name was Mildred Cecilia Harriet Sturt, and she was born in 1869. Unfortunately, we don’t know many details of her life. As is the case with many female members of the British gentry during Victorian times, most of what we know about her is what we might call genealogical information – who her parents were, whom she married, and the names and dates of her children.

We know that Mildred Cecilia Harriet Sturt was the daughter of Henry Gerard and Augusta Sturt, the first Baron and Baroness Alington of Crichel. She grew up in Dorset, England, and, in 1892, the 24 year-old Mildred married a Conservative Member of Parliament and former army officer named Henry Arthur Cadogan, the Viscount Chelsea. Suddenly, the young Miss Sturt had become the Viscountess Mildred Chelsea, a mid-level member of the British nobility in her own right. She had six children with the Viscount – five daughters, and a son – before her husband died of cancer at the age of 40 in 1908. One of her daughters married into the Spencer-Churchill family – Spencer like Lady Diana Spencer; Churchill like…Churchill. Another daughter married into the Stanley family, of Stanley Cup fame. Two years after her husband’s death, in 1910, she married a British naval officer named Hedworth Lambton Meaux, and a year after his death in 1929 she married her third and final husband, Charles William Augustus Montagu. Their wedding took place at Kimbolton Castle, the final home of Henry VIII’s wife, Katherine of Aragon. So I guess you could call her Mildred Cecilia Harriet Sturt Chelsea Meaux Montagu. She lived until 1942, when she died in London at the age of 73.

That, in short, is what we know of Mildred Chelsea’s life.

But there’s one other detail that we know about her. One day, sometime between 1899 and 1910, the young Viscountess Chelsea – then in her 30s – read a small book of poetry. It was probably a spring day, and as I imagine it, the sun was shining, she was wearing a simple but elegant white dress, and she had taken a walk on the grounds of her estate, or perhaps at a local park down by the water.

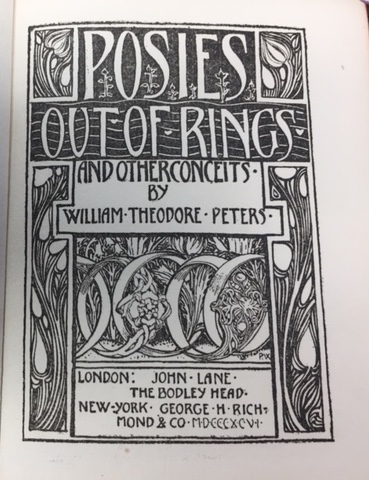

Sitting on a bench, Mildred pulled out a small, leather-bound volume of poetry, entitled Posies Out of Rings and Other Conceits, by William Theodore Peters. You may never have heard of the book Posies out of Rings and Other Conceits, and that’s probably because of what we might charitably call the “quality” of the poetry it contains. In the book, you can find such memorable compositions as this one, called “Betty’s Eyes”:

Betty’s eyes are violets

Violets where sweetness lies

Promises she may not keep

Lurk in Betty’s flower-like eyes.

And if you like that one, well then you’ll love “Star and Flower.”

The Star of Love is a flower, a deathless token

That grows beside the Gate of Unseen Things.

A daisy is a fallen star, a thought unspoken

Written by one whose wings are silver wings.

You get the idea.

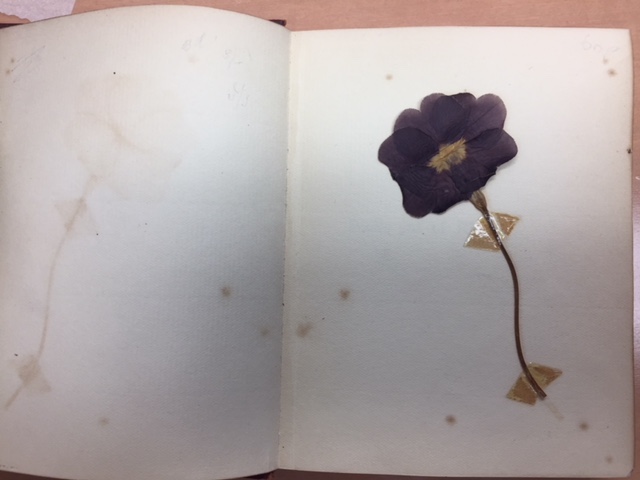

For whatever reason, flowers must have been on Mildred’s mind that day – maybe because of the “Posies” in the title of the book, or maybe because of the poem reminding her that “The Star of Love is a flower.” For whatever the reason, before Mildred put that book of poetry away, she noticed that there were some wildflowers growing nearby. Getting up, she walked over to where they were, bent over, picked a small purple one, and laid it between the pages of the book where it could dry flat.

That little incident isn’t written up in her biographical record, of course. How do I know about it? I know about it because I have the book that right here – I purchased it several years ago at a used bookstore in Victoria. Here is the title page, indicating that the book was published in 1896, here is Mildred Chelsea’s bookplate, and here is the flower that she picked and pressed between its pages (the flower is what sold me on the book).

Think about it. More than a hundred years ago, a young woman – maybe without thinking about it very much at all – bent over and picked a flower, perhaps reasoning that it would be nice to look at later sometime. And now, half a world away and a over century later, hundreds of us here in this room are benefitting from her decision to do so.

How many things that you do during your life will last a century? How much of what you do will have people smiling a hundred years from now? Will any of it continue to inspire people in a century…or at least have any effect whatsoever?

Some things certainly will continue to benefit people in the long-term. If you build a building, or have grandchildren, or write a book, there’s a good chance that, in a century, at least someone is going to remember what you’ve done. But most of what we do won’t be that memorable. A hundred years from now, nobody will remember that you brushed your teeth this morning (though if you never brush your teeth, they may remember that!). They won’t remember that you bought furnace filters, or paid your electric bill, or went out to a nice restaurant with your friends.

So much of what we do is in the realm of the forgettable; so little of it is eternal.

The forgettable, of course, isn’t necessarily bad. Going out to dinner with your friends can be very nice, and it’s important to buy your furnace filters. But the question is whether we want these types of activities – the forgettable ones – to be the sum total of our existence. As you reflect upon your life, don’t you think that it would be nice if at least something of what you do during your limited time here on earth could outlast you? Wouldn’t it be nice if the reach of your life’s activities could extend beyond the years of your life? It was so wonderful that Mildred Chelsea left us that flower; wouldn’t it be great if a hundred years from now, someone, somewhere, could say something similar about something that you’ve done?

The problem, of course, is that it can be difficult to figure out what’s memorable and what will end up forgotten. After all, we never know whether the things we do in life will have staying power, or not. When Mildred Chelsea bent over to pick up that flower a little over a hundred years ago, I don’t know exactly what she was thinking, but I think it’s safe to assume that one of the things she wasn’t thinking was, “Oh look, a flower. I should press it between the pages of my book, because 110 years or so from now, a rabbi in Calgary Alberta will be able to share that flower with his congregation.” No, she probably had no clue about the power of that flower; she probably had no idea that what she was doing had left the realm of the forgettable and entered realm of the immortal.

We can’t ever know whether the memory of what we do will outlive us, but we can certainly try to fill our lives with that type of activities. Or maybe we could put it another way. There are no guarantees that what we do will be remembered – we have no control over that. But what we do control is whether our activities are worthy of being remembered. If you want, you can fill your life with the mundane – getting yourself showered and dressed in the morning, running your errands, attending that endless series of meetings at work. But if you want, you can also fill at least part of your time with things that have more eternal significance – working on behalf of an important cause, fighting for justice, committing random acts of kindness. And when you get really good at it, you can also figure out ways to transform the ordinarily mundane acts of life into deeds that are truly memorable. You’ll take a detour on your daily errands to drop off a surprise little gift at the home of a friend who’s feeling down; you’ll make something magnificent out of the time you spend in those work meetings; or maybe you’ll just be able to contextualize buying those furnace filters, seeing it as part of what it takes to create a warm, safe home for your family.

Of course, Judaism is all about getting us to spend our time on things that are worthwhile rather than on things that are trivial, but in Judaism, we use different language to describe those activities. In Judaism, we’re supposed to be holy – kadosh – rather than it’s opposite – chol – mundane, or humdrum.

In fact, we chanted words echoing this sentiment earlier tonight. Just a little while ago, we said, “V’ahavta et Adonai Elohecha, b’chol levavcha, uv’chol nafsh’cha, u’vchol m’odecha. You should love Adonai your God with all your heart, with all your soul, and [to translate literally] with all your very,” with all your oomph. How are we supposed to love God? In Judaism, we love God by doing what it is that God wants us to do. And how do we know what God wants us to do? We read our sacred texts, and there in the Torah we find 613 things that God wants us to do – the 613 commandments, mitzvot, of our sacred scripture. God wants us to give some of what we have to those in need. And God wants us to be faithful to our spouses. And God wants us to take care of the earth, and to come and worship together on Jewish festivals just like we’re doing now. And as the sun goes down on Shabbat, God wants us to light candles against the darkness.

More generally, if you read those old books, you’ll find that God wants us to create a world that is kind, and just, and compassionate. God wants us to build strong Jewish communities. God wants us to be good to ourselves and to every human being, because we each carry a spark of the divine within us. And doing all of these things are the ways we in Judaism show our love to God.

And remember, we’re supposed to love God with all our heart, and with all our soul, and with all our oomph. That leaves no heart, soul, or oomph for anything else at all. We Jews have one thing to do in life, and one thing only, and that’s to love God. When we do it right, we love people, and we love the world around us, as well, for that’s what our tradition means when it tells us to love God.

God wants us, in other words, to do things that are worthy of being remembered. God wants us to leave flowers of all kinds for the generations yet to come.

According to Judaism, as I mentioned last week on Rosh Hashanah, every time a Jew fulfills a mitzvah, every time we do something that God wants us to do, we move the world closer to fulfilling our great messianic dream of the future, and that’s an act that is worthy of being remembered. Making the world better is a gift that can be our greatest bequest to future generations.

It is an important message, I think, and it’s particularly important for us to remember that message now. Nowadays, our fellow human beings are reeling in the wake of horrible natural disasters – in Houston, in Florida, in Mexico, Puerto Rico, and elsewhere. And many of those disasters were due to at least in part to humanity’s mismanagement of the earth’s precious natural resources. Closer to home – in Waterton, in British Columbia, and elsewhere, fires have ravaged the land in recent months, and we didn’t even have to turn on the TV or read the papers to learn of those disasters. Here in Calgary, if you’ll recall, all we had to do was look at the pall of smoke that descended on our city, and smell the choking fumes that it brought. These fires, too, were partly a result of the vulnerability we humans have created by heating up the world around us.

God put Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden to till it and to tend it. Have we forgotten this sacred call to all humanity to take care of our world? When our grandchildren’s generation comes of age, will there be any more flowers left to pick?

Nowadays, our fellow human beings are showing up on the shores of this country and others in search of safe haven, fleeing violence and oppression in their native lands. South of us, the president of the United States rants on about building walls and closing the gates of that country to people in need of safety. Here in Canada, we can take pride in the fact that our country is more open to refugees, and yet, there are voices around us saying that we should close the gates, that we should be concerned about our own people before worrying about others…as if it’s an either/or proposition.

Sadly, some of those voices have even come from within our own congregation. We have a group of heroic volunteers who took in and supported a family of Syrian refugees, and there were those right here at Temple B’nai Tikvah who said that we need to help Jews before we help others…as if it were an either/or proposition. As a community, we should have no tolerance for such a sentiment. Yes, it’s true, to paraphrase the words of Hillel, if we are not for ourselves, who will be for us? But the second part of that statement is also true – if we’re only for ourselves, what are we? We Jews aren’t at liberty to be concerned only for our own well being. We need to be concerned about the rest of the world, too. For us, it’s never an either/or proposition. To be a sacred people means remembering that it’s always a both/and.

Nowadays, people around us continue to struggle economically; nowadays, the clouds of nuclear conflict are beginning to form over the Korean peninsula; nowadays, families around us – some right here in our own community – struggle to stay together, even as they put on a smiling façade to hide their problems from their neighbors.

Nowadays, there is a screaming, howling need for you to do devote your time and energy to sacred work. The earth needs you to heal it; people need you to take them in; families need your help in facing the mounting economic and emotional stresses that plague them.

In short, if you want your life to matter, if you want to reach beyond the mundane and truly do something of lasting significance with your time on earth, then now – especially now – you’ve got to do mitzvot. A mitzvah, remember, is not just a good deed. It is, instead, the fulfillment of a sacred commandment. To do a mitzvah is to do something holy – something precious, and noble, and sacred, and certainly beyond the mundane.

Be kind to other people. Come here to Temple and help us in any one of our many social action activities. Come to services and lend your voice to our sacred song. And when it gets really dark, then join us in lighting candles against the gloom.

Being Jewish is all about doing things of genuine and lasting significance in a world that so often gets mired in the mundane and the trivial. You should be proud to be an inheritor of such a sacred tradition. May the fires and the storms around us continue to remind you of the importance of realizing our tradition’s sacred truths.

Early in the last century, Mildred Chelsea picked a flower, and now we can all still enjoy its beauty. What flowers will you leave behind for future generations after you’re gone? Let’s turn to one another, and let’s turn to our glorious Jewish tradition, and together let us figure out how to leave precious and magnificent bouquets for the generations that will come after our own.

That way, this year, as well as future years, can truly be a shanah tovah u-metukah, a good sweet new year for us all.

Shanah Tovah.