Scrolling Forward: The Torah, Its Role in Jewish Life, and Our Next 40 Years

Rosh Hashanah Morning Sermon

Temple B’nai Tikvah

5779/2018

By Rabbi Mark Glickman

There are a lot of things that I do very quickly, just to get them done, but when it comes to at least one thing, I’m very methodical. I eat oranges very slowly. It makes my family crazy.

Let me tell you how I do it – because I know you’re interested. First, I start with a big, juicy navel orange. I get out a small plate or a bowl, and a knife. The knife can’t be too large, or to small, and it needs to be sharp – I’ve found that a serrated steak knife tends to work best. Then, since this is going to take a while, I sit down in front of the TV. The show that’s playing needs to be good, but not too good, because I need to be able to take my eyes off the screen periodically to look at what I’m doing. The news or Seinfeld reruns tend to work best. Then, to begin, I take the knife, and very carefully cut through the peel around the top stem, cutting deep enough to slice through it, but not so deep as to penetrate the fruit itself. Yes, it’s true. I start by literally circumcising the orange.

If you do it right, you can remove the top part of the peel, and along with it will come the pith – the white stuff on the inside of the skin – all the way down to the core of the fruit. It’s great when that happens. Then, I carefully make a few downward incisions from the top of the remaining peel, maybe an inch long or so. This allows me to carefully work my fingers under the orange peel, and pull it away from the fruit. If at any point during this process, you penetrate the membrane covering the fruit so that juice starts to flow, you’ve ruined the orange – give it away to someone who doesn’t care about the integrity of this process, and start over again.

Once you’ve removed the peel, carefully remove any remaining pith from the orange. You might need to use the tip of your knife to get it off. By now, Seinfeld is coming to an end, or the news is airing its final human-interest story, and you’re getting close to being able to eat your orange – but you’re still not quite there yet. Carefully insert your thumbs in the center hole on top of the orange, and pull it apart. It’ll be easy, because by now your family will have long ago abandoned you and left you alone in the room. If, while you’re separating a section of the fruit, you break the membrane and the juice starts to flow, then track down a family member, give them the fruit, and start again.

If, however, you succeed in juicelessly removing sections of fruit, then you’re ready: “Baruch atah Adonai, Eloheinu melech ha-olam, borei p’ri ha-etz. Blessed are you, Adonai our God, Creator of the fruit of the tree.” Then, eat your fruit. I can tell you, when you prepare your orange this way, it will taste sweeter than any ever before.

Why my obsessive attention to detail here? Because I love eating those oranges. They taste so sweet, and I relish each and every bite. I eat a lot of food on the fly – quickly and without thinking much about it. But oranges are different. I take my orange eating seriously, and when I do, I enjoy every single moment of the process.

Now, maybe some of you think this is foolish. “Glickman,” you might be saying, “why don’t you just peel the darn orange and eat it. You could be done even before the newscasters finish the top stories, and the orange would still taste just the same. Why do something so slowly, when you could accomplish just the same thing far more efficiently.

Well, if you feel that my nuanced and refined method of orange consumption is foolish, I’d like to point out that we as a community do something that many outsiders might see as equally foolish. I’m referring, of course, to the scrolls that sit in the ark just a few feet behind me even as I speak. As you know, we live in an age of desktop publishing and high-speed printing, and yet, every week right here in this building – either in this room or in the small chapel down the hall – we read out of a book that takes a long time to make. It makes my orange-eating seem lightning-fast by comparison.

As a text, the Torah exists in all kinds of formats, many of which are easy to create, quite affordable, and would be easier to read from during services. There are hardcover Torahs, paperback Torahs, bound Torahs with vowels, bound Torahs without vowels, and bound Torahs both with and without vowels. There are Torahs with commentaries, and Torahs without. There are Torah translations in Old English and Modern English and Hipster English, as well. There are Torahs in every language from Korean to Kazakh to Klingon. There are beautifully bound Torahs, collector’s edition Torahs, and Torah apps for your smartphones and iPads. And if I wanted, I could go down the hall right now, call a Torah up from the internet, and have the whole thing printed out for you in just a few minutes.

Yes, the Torah is one of the most accessible texts ever, often in neatly packaged, very convenient, and eminently affordable formats.

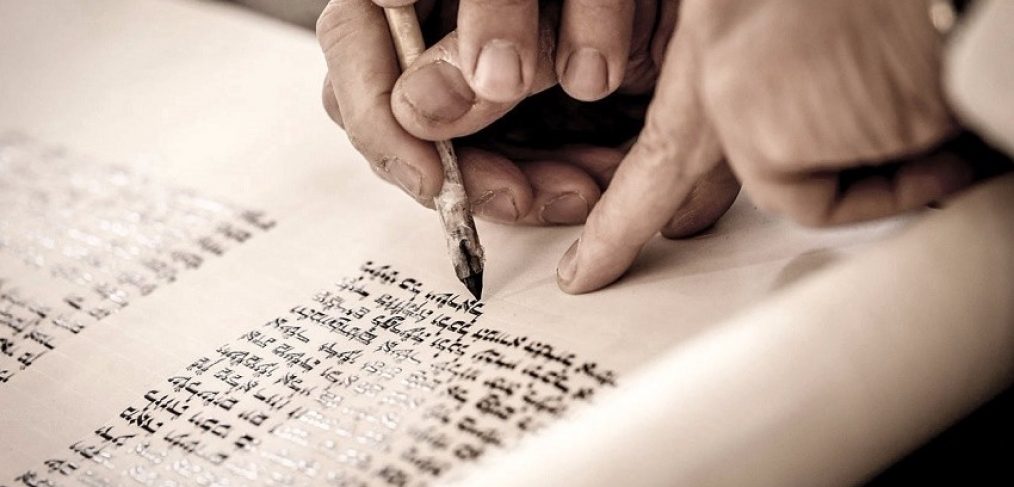

And yet, every week, and on holidays, too, we come into this room or into our small chapel and read the thing out of a bulky, unwieldy scroll, handwritten with a feather quill onto parchment.

In case you don’t know, let me describe to you what goes into making one of these scrolls. Each scroll, as you may know, is painstakingly created by a scribe using a feather quill. There aren’t a whole lot of scribes these days – the work takes a lot of training, there isn’t a huge market for it, and most scribes are therefore reluctant to take on apprentices. Sadly, most scribes these days are men, although, fortunately, there are some women getting involved in this work now, too. Most of a scribe’s work typically involves making Torah scrolls, mezzuzahs, and tefillin, though when they train, they practice by making Scrolls of Esther. You see, if a scribe makes a mistake, he or she can often fix it, but if the mistake is on one of the names of God used our sacred texts, then the scribe has to scrap that whole piece of parchment and start over again. Scribes don’t like it when that happens. And because the megillah – the Scroll of Esther – is the only book in the bible that doesn’t explicitly mention God by name, it’s a good place for scribes to cut their teeth in this painstaking work.

To create a Torah scroll, the scribe takes a specially treated piece of parchment and, using a stylus, carefully etches barely visible lines into the parchment guide his writing – two vertical lines and, typically, 42 horizontal ones for each column. Then, to prepare the ink, the scribe mixes together several ingredients – oak galls, gum arabic, copper sulfate, and soot. Oak galls, as you all know, are small pods made by the secretions of wasp larvae growing on the branches of oak trees. Gum arabic, of course, is the sap of an acacia tree. It takes only about a cup of ink to make an entire scroll, but that’s deceiving. The scribe mixes the ink special for each parchment so as to maximize its power to grip onto the writing surface and hold on tight.

Before even beginning to write, the scribe immerses in a mikvah, writes out the name “Amalek” on a scrap of parchment, and crosses it out. Amalek, you see, was one of the worst bad-guys in the bible. The Torah commands us to blot out his memory, and the scribe does just that before commencing work each day.

Then, the scribe recites a blessing, and begins to write. The scribe will never write from memory, but instead will check each letter in a book called a Tikkun before writing it. He or she will check the letter, chant its name, and write it on the parchment. Then the scribe checks the next letter, chants its name, and writes it on the parchment. Over and over and over again.

As you know, the Torah scroll contains the text of the Five Books of Moses. Those five books consist of 54 weekly Torah portions, which are in turn made up of 187 chapters, and those chapters are subdivided into 5,844 verses. The verses consist of 79,976 words, and those words are in turn made up of 304,805 letters. 304,805 letters.

And because I know you’re so fascinated by these statistics, I’ll continue. Of those 304,805 letters, 27,057 of them are alefs, 17,344 of them are bets, 2,109 of them are gimmels…. Would you like me to continue?

In the most common Torah format these days, all those letters are arrayed into 254 columns of text, and I’m told that a solid day’s work for a scribe will yield one of those 254 columns. That’s 254 days of writing for a single scroll. Add in Shabbat and holidays, as well as several days of proofreading, and you can see that it takes a scribe about a year to create one of these scrolls.

Yes, I think we can safely say that the Torah scroll is the Glickman orange of Jewish ritual life.

So, still, we’re left with the question. Why bother? Printing a Torah scroll would be so much easier that writing one out. Buying a Torah in book form would be so much more affordable than getting a handmade scroll. And frankly, using a bound book would be far, far easier than using a scroll – a book would be lighter, a book would make it easier to find our place, a book wouldn’t demand nearly as big an ark as a scroll does.

In order to answer that question, I invite you to reflect on the role that Torah plays in Jewish life. We Jews consider the Torah to be the greatest gift that God has ever given our people – even better than gefilte fish, and bagels and rugelach. Our tradition teaches that the answers to all of life’s most profound questions can be found in that book – we just need to study it right. How can I balance between work and family? What’s my place in the world? What does it mean to live a good life? Study the Torah, and you’ll find wisdom, and guidance, and, yes, with the right kind of incisive reading, you can even find answers to those questions. They say that life doesn’t come with an instruction book, but for Jews it does – and we write it on a scroll and we keep it in an ark and we rise before it whenever we take it out.

That’s why our tradition is so full of rich metaphors for Torah. “It is a tree of life to those who hold it fast, and all who cling to it find happiness.” Think about it – a tree of life; hold onto it, and you’ll be happy. In Judaism, Torah is fire – aish haTorah. It warms us; it energizes us; and if we’re not careful, it can burn us, too. Alternatively, in Judaism, Torah is water – it nourishes us; it cleanses us; it falls down like dew from the heavens. The Torah is love – God loves us so much that God gives us this wonderful treasure as a gift. God loves us like a parent, and gives us the Torah’s rules. God loves us like a teacher, and gives us the Torah’s wisdom. God loves us like a friend, and tells us great stories that we can tell over and over again, finding new meaning in them each time.

More profoundly, the Torah is the way we connect with God. As Rabbi Louis Finkelstein once said, “When I pray, I talk to God. When I study, God talks to me.” In Judaism, we don’t climb to a mountaintop to hear the voice of God, nor do we even sit down here or at home and pray. No, in our tradition, to hear the voice of God we study Torah.

Christians have Jesus as their conduit to God. We have Torah. It is that central in Jewish religious life.

We sing the words in every evening service. “Ahavat olam beit yisrael amcha ahavta. You have loved Your people, the house of Israel, with eternal love.” And how did You express that love? “Torah umitzvot, chukim umishpatim otanu limad’ta. Torah and commandments, laws and statutes you have given us.” Torah is nothing less than an embodiment of God’s love for each and every one of us.

So yes, we cherish our Torah scroll. We dress it in beautiful clothing and adorn in with precious decorations. We rise whenever we open the ark. We carry the Torah around the congregation, and many of us kiss it. We’re careful never to drop it, and we sing its praises over and over again whenever we gather for worship.

Why our seemingly obsessive attention to these bulky scrolls? Because we love studying their words. We love these words – I can’t believe I’m saying this – even more than I love my oranges. They taste so sweet, and we want to relish each and every one of them. I read many words on the fly – quickly and without thinking much about them. But Torah is different. We take our Torah seriously, and in so doing we make the most of each and every one of its wonderful words.

We here at Temple B’nai Tikvah have our own scrolls, each of which has its own story. One scroll we inherited from the Jewish community of Medicine Hat, Alberta when their synagogue closed. Another was originally in Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan, and then went to Regina before it finally made its way here. A third scroll is one of the famous “Westminster Scrolls.” It survived the horrors of the Holocaust, and was then restored at the Westminster Synagogue in London before finally coming here to Calgary. And the big scroll – the one we use for our Shabbat and holiday Torah readings – was donated by a non-member. It was only after Ron Bing went to pick it up that the donor said he was only giving half the money – Ron had to scramble to raise the rest of it in short order. (I’m skipping many details of that story – I’m sure Ron will gladly supply them to you later if you want to hear them.)

Of those scrolls, one is on long-term loan to a congregation that needs it in the States, two aren’t really kosher (old scrolls often suffer from fading or chipping ink, which renders them unusable). That leaves just the big one that we read from during services. It’s heavy – and that makes it difficult to use sometimes, but its script is dark and clear and beautiful. Its’ the one we use every week, and we love it.

This year, as you know, our congregation will celebrate its 40th anniversary. We started as a group of just 13 families meeting in the Bings’ living room, and over the years, slowly we grew. It took hard work and commitment on the part of many people, several of whom are with us here this morning. The congregation got its Torah scrolls, eventually moved to the JCC, and finally, through a lot of hard work and commitment – not to mention money – we moved to this building. Along the way, this congregation has become the center of Reform Jewish life in Calgary. We’ve gathered together on Shabbat and holidays, we’ve studied Torah together both as adults and as children in our religious school. We’ve celebrated weddings, Bar and Bat Mitzvahs and other simchas with great joy, and we’ve wept and comforted one another in times of grief and difficulty, as well.

I’ve spoken with many longtime members of our congregation, and I often ask them what the greatest moment or moments were in the history of Temple B’nai Tikvah. More often than not, the veteran members of our congregation respond that the most exciting time to be a part of Temple was when we moved into this building. This little group, once small enough to meet in a modest-sized living room, had grown, pooled its resources to purchase a synagogue home, and thus literally put itself on the map. Moving into this building not only meant that we’d have more room in which to conduct our activities, but it also signified our having made it in this community. Reform Judaism now had its own address – right here on 47th Avenue. Right here beneath these beautiful kippot and the eternal light that illumines them. Right here, before our own ark and the Torah scrolls it holds.

That was a great accomplishment, and this congregation – its leaders and all of its members – should feel proud for having made it. And now that we’re here, and now that it’s time to begin looking ahead to the second forty years of our existence, we have an opportunity to do something else that’s really amazing.

My friends, this year, we are going to celebrate our fortieth anniversary, and we’re going to do it with gusto! Betsy Jameson and a team of volunteers are hard at work planning a major celebration for next spring, and you’ll be getting details about that soon. And additionally, we’re going to something else to celebrate this milestone birthday – something that, on the one hand, we’ve never done before, but on the other, affirms and celebrates what is most important to us as a synagogue community devoted to the ideals of Judaism.

My friends, to celebrate our 40th anniversary, we’re going to make a Torah.

Here’s what’s going to happen. A group out of Miami called Sofer on Site (“sofer” means scribe) is going to help us identify a scribe in Israel who will do the bulk of the work on our Torah. But before that work starts, one of the scribes is going to come here and be with us as we kick off this project. Each and every one of you – as individuals or as family groups – will have the opportunity to guide that scribe’s hand as he carefully pens one of the 304,805 letters of the scroll. If you want, you can even sponsor one of the letters in that scroll, or a word, or a verse, or a Torah portion, or even a whole book. And with the resources that we raise in the process, we’ll be able to guarantee our ability to remain a center of Torah here in Calgary for a long, long time in the future. With the help of a group of generous donors, we’ve already raised the seed money for the project itself. Now, as we create this new Torah, we can build for the future.

Working with Sofer on Site, we’re going to see blank parchment, and we’re going to help transform it into a sacred object. And in the future, our young people will read out of the scroll we create during their Bar and Bat Mitzvah ceremonies. Our congregation will read its words on the holidays. Our community will cherish it as it sits in the most central spot in our sanctuary – right here in the aron hakodesh, the holy ark.

Along the way, we’ll learn more about how a Torah is created. We’ll learn about the role it plays in Jewish life, and how we can play our own role in its creation.

This year, you and your family will each have your own letter – or your own verse or chapter or book – in what will become our Temple B’nai Tikvah Torah scroll. And as a result, our congregation will be able to study that letter and many others for generations yet to come. Torah scrolls typically survive for a few centuries. Not only will you study from this scroll, but so too will your children, and grandchildren and countless others many generations from now.

My son Jacob once participated in a similar project at Camp Kalsman – the Reform Jewish summer camp near Seattle where he worked. Not long after that, I told my son that I was planning to see that same scribe at another event I was attending. “Oh,” said Jacob “tell him I said hi. And if he forgets who I am, just remind him – I’m mem.” That was his letter – the letter he made in the Torah scroll. What will be your letter in our scroll?

Even though there are 304,805 letters in the scroll, one rabbinic tradition teaches that there are actually 600,000 letters in it – one for every Israelite who made the exodus from Egypt. One of them will be yours. Which one that is will be up to you and the rest of us to figure out.

Torah has always sat at the very heart of Jewish existence. We have embraced its holy words, dancing with them during times of celebration, and carrying them with us as we’ve fled burning towns and villages. It’s considered a mitzvah for each Jew, at some point in his or her life, to create a Torah scroll of his or her very own. This year, we as a community are going to do just that. More details will be coming soon, but it promises to be the experience of a lifetime for us all.

We’re going to make a Torah this year, and in so doing, we’ll make the words very sweet indeed. Just like eating my orange, it’s going to be a long, slow, and wonderful process – one whose fruit will last here in our beloved Temple for many generations yet to come.

For now, however, let’s continue our Rosh Hashanah celebration by doing something we Jews love to do. Let’s read some Torah.

Shanah Tovah.